Can NRCan’s Learning Organization Community of Practice (LOCoP) be thought of as an apprentice program for leaders?

Recently, I attended a half-day session with David Snowden, author of the Cynefin framework for solving problems. Snowden makes a distinction between how one should solve complex problems, versus how one should solve simple or merely complicated problems. I won’t go into details here, but suffice it to say, that in a knowledge-based economy where innovation is required, we need the type of people who can solve complex problems. In other

words, we need chefs, not recipe users!

Snowden made the point that there is a big difference between a chef and a recipe user. Sure, if you have all the right equipment in your kitchen, you lay out all the tools and necessary ingredients and you have a good recipe to follow, then just about any competent person can

produce a reasonably good meal. But only a chef can walk into your kitchen, see what’s in the fridge, and create a truly exceptional meal.

The difference, Snowden asserts, is that chefs possess practical wisdom.

Wisdom is the ability to reflect on one’s knowledge or experience. Practical, here, means it was acquired through the process of practice – in a chef’s case, as an apprentice.

The beauty of the apprentice model is that it allows someone to imperfectly mimic the master and make mistakes. Studies have

shown that people recall far more knowledge when they actually act on their knowledge than when they just think about it. In an apprenticeship program, one practices what one has learned from books, but in an environment where it is safe to make mistakes. The result is a much greater ability to recall and reflect on that knowledge for innovative results.

Snowden also made the point that doctors and lawyers also use the apprentice model, but managers have no such system; instead they have the MBA.

That’s when I stated to re-think the role of our Learning Organization Community of Practice as an apprentice program for leaders. When I first took my LOCOP training, I came out of that training thinking of myself as an apprentice - but an apprentice in facilitation. Now, I recognize that I am really an apprentice in becoming a leader.

Every time I use my LOCOP facilitation tools to develop a shared vision in a team, to think about the whole puzzle at once, to create space for new learning, to foster deep reflective listening and build shared meaning in conversation rather than argument, I am conducting a small, safe-to-fail exercise in which I practice the theory I learned in my original training. The result is that I now have a bucket of tools in my back pocket that I can mix and match and modify to solve all kinds of problems in a collaborative and increasingly innovative way.

Add to that the value of having a community who I can learn new techniques from, who I can validate my own ideas with, and who I can call on to help me solve tough problems, then I think we have many of the essential elements of a low-cost apprentice program for leaders right in my place of work.

Friday, October 28, 2011

Saturday, October 15, 2011

A knowledge management conundrum: how to share secret information

One KM issue that has sat in the back of my mind for some time is how to share information among employees that is classified as secret.

We spend a lot of time in our workplaces implementing document management solutions like SharePoint, writing collaboratively on wikis, fostering knowledge exchange through communities of practice, etc. - basically trying to make the knowledge contained in the organization findable and retrievable to contribute to evidence-based decision making

But none of these tools can address the issue of how to share secret information. Documents classified as secret hold a wealth of valuable data, opinion and insight, and should be a part of an organization's evidence base for decision making in a form that is findable and retrievable to the person with the right security classification and a clearly demonstrated need to know.

That's the thing about documents classified as secret; they can be shared with someone if the recipient has a clearly demonstrated need to know, but cannot be made freely available to people to trawl through on the possibility they might find something useful - even if the searcher has a secret-level security clearance.

Not surprisingly, this is not a new challenge for intelligence organizations. Recently, I participated in a workshop with David Snowden, who gave me some insight into how US intelligence agencies deal with this challenge.

According to Snowden, in the CIA of a few years ago, when an intelligence officer would receive a piece of intelligence to review, say an intercepted phone call or email, they would analyze it, write a short report about it, and file it. It was difficult to share the information, particularly among agencies, because it was all secret. Connecting the dots between pieces of intelligence to create a big picture view generally relied on officers remembering what they read. But sometimes, they might have read it years ago.

So instead, the CIA started a process whereby when an officer received a piece of intelligence, the officer would index the intelligence using carefully constructed quantitative indexes (kind of like key words, but more sophisticated. For example, an index might ascribe a weight to a piece of intelligence that depends on whether the intelligence is associated with the Middle East, Europe, or North America ).

Because each intelligence piece now has quantitative indexes associated with it, the data can be analyzed statistically or plotted on a 2-D or 3-D graph to search for patterns. When patterns emerge, such as a cluster of data points, the records associated with these data points can be requested by the intelligence officer because he can clearly demonstrate a need to know.

Furthermore, this quantitative metadata about the intelligence records can be shared with other agencies, who might filter it or analyze it in different ways, or add their own data to search for other patterns. If they find a pattern, they can request the relevant records because they have the appropriate clearance level and can clearly demonstrate a need to know.

In my own organization secret documents are locked away in secure cabinets or stored on computers that are not connected to the network. Even worse, documents may not be declassified when the need to keep them secret no longer exists. No matter how useful a Memorandum to Cabinet, for example, might be to me, I have no way to know it even exists.

So now I am wondering if it would be possible in my own organization to have every secret document indexed by the author and the metadata made available for analysis. If so, a whole world of organizational knowledge could be made available to those with a need to know to inform evidence-based decision making.

We spend a lot of time in our workplaces implementing document management solutions like SharePoint, writing collaboratively on wikis, fostering knowledge exchange through communities of practice, etc. - basically trying to make the knowledge contained in the organization findable and retrievable to contribute to evidence-based decision making

But none of these tools can address the issue of how to share secret information. Documents classified as secret hold a wealth of valuable data, opinion and insight, and should be a part of an organization's evidence base for decision making in a form that is findable and retrievable to the person with the right security classification and a clearly demonstrated need to know.

That's the thing about documents classified as secret; they can be shared with someone if the recipient has a clearly demonstrated need to know, but cannot be made freely available to people to trawl through on the possibility they might find something useful - even if the searcher has a secret-level security clearance.

Not surprisingly, this is not a new challenge for intelligence organizations. Recently, I participated in a workshop with David Snowden, who gave me some insight into how US intelligence agencies deal with this challenge.

According to Snowden, in the CIA of a few years ago, when an intelligence officer would receive a piece of intelligence to review, say an intercepted phone call or email, they would analyze it, write a short report about it, and file it. It was difficult to share the information, particularly among agencies, because it was all secret. Connecting the dots between pieces of intelligence to create a big picture view generally relied on officers remembering what they read. But sometimes, they might have read it years ago.

So instead, the CIA started a process whereby when an officer received a piece of intelligence, the officer would index the intelligence using carefully constructed quantitative indexes (kind of like key words, but more sophisticated. For example, an index might ascribe a weight to a piece of intelligence that depends on whether the intelligence is associated with the Middle East, Europe, or North America ).

Because each intelligence piece now has quantitative indexes associated with it, the data can be analyzed statistically or plotted on a 2-D or 3-D graph to search for patterns. When patterns emerge, such as a cluster of data points, the records associated with these data points can be requested by the intelligence officer because he can clearly demonstrate a need to know.

Furthermore, this quantitative metadata about the intelligence records can be shared with other agencies, who might filter it or analyze it in different ways, or add their own data to search for other patterns. If they find a pattern, they can request the relevant records because they have the appropriate clearance level and can clearly demonstrate a need to know.

In my own organization secret documents are locked away in secure cabinets or stored on computers that are not connected to the network. Even worse, documents may not be declassified when the need to keep them secret no longer exists. No matter how useful a Memorandum to Cabinet, for example, might be to me, I have no way to know it even exists.

So now I am wondering if it would be possible in my own organization to have every secret document indexed by the author and the metadata made available for analysis. If so, a whole world of organizational knowledge could be made available to those with a need to know to inform evidence-based decision making.

Thursday, July 21, 2011

The rise of the networked enterprise: Web 2.0 finds its payday

A recent report by McKinsey & Co.claims to show, using a proprietory survey of over 1000 company executives, that companies that incorporate Web 2.0 technology to increase collaboration see greater growth in market share and other economic indicators. The majority of respondents to the survey say that their companies enjoy measurable business benefits from using Web 2.0, including increased speed of access to knowledge, reduced communication costs, increased speed of access to internal experts, and increased customer satisfaction.

The report goes on to say:

The report goes on to say:

Moreover, the benefits from the use of collaborative technologies at fully networked organizations appear to be multiplicative in nature: these enterprises seem to be “learning organizations” in which lessons from interacting with one set of stakeholders in turn improve the ability to realize value in interactions with others. If this hypothesis is correct, competitive advantage at these companies will accelerate as network effects kick in, network connections become richer, and learning cycles speed up.This appears to be another example of how the business world has gone beyond just looking at collaboration or Web 2.0, and is starting to focus on the more important outcomes of using this technology.

Monday, July 18, 2011

Social Learning at Telus: Linking collaborative technologies to learning strategies

Recently someone sent me a link to a video clip of Dan Pontefract, Director of Learning and Collaboration at Telus, talking about the social collaboration tools they have put in place to encourage the sharing of information and knowledge. The video is only 2.5 minutes long and is well worth watching.

Telus is not unlike a lot of other organizations, including my own, who have put in place collaboration tools like wikis, forums, blogs, filesharing, instant messaging to promote the exchange of knowledge. But a few things about Dan Pontefract's presentation really struck me.

It's about Learning, not just collaboration

For me, the key point in Dan Pontefract's presentation is that collaboration technology is intimately connected to employee learning. By creating platforms like team collaboration sites, blogs, microblogs, videosites and wikis where employees can share ideas, opportunities and issues, employees are continuously learning from one another. He sums it up well when he talks about the "Learning 2.0 Model" at Telus. "Learning", he says, "is part formal, part informal, and part social." At Telus social learning is facilitated through social media. Eventually, as people begin using the technology, they get into a rhythm of how they start sharing and how they start exposing their content, their knowledge and their ideas. Ultimately, he argues, people realize quickly that what they gain from everyone else helps them do their job faster, better and in a more engaging fashion.

Note, however, that while Social media is facilitating one type of learning at Telus, it has not replaced other more formal and informal modes of learning - the so-called "sage on a stage". Formal and informal learning, no doubt, continues to play an important role in Telus' employee learning strategy.

This is not the first time I have seen Web 2.0 collaboration tools linked to employee learning strategies in organizations. At a recent conference on knowledge management, I met the director of learning for Rogers Communications, who told me a very similar story about what they are doing. As with Telus, social learning plays an important part of their employee learning strategy, but it is linked to formal and informal methods of learning. A similar story was told by Sierra Wireless at the same conference.

What really strikes me in these examples is the connection of collaboration to employee learning. In other words, collaboration is a tool, a means to an end that facilitates learning, but collaboration is not the objective. The objective is to create a learning organization.

Meanwhile, in government these days, I see a lot of attention being paid to social media and collaboration, but I have not yet seen this formal link to employee learning strategies. So, while we have wikis, blogs, forums, video sharing sites, file sharing sites, and other tools, and while timely access to information is routinely touted as the key benefit, it is not at all clear that this is seen as a form of social learning or how this social learning is linked to more formal and informal learning in each employees learning objectives. In fact, I wonder if recent events like the wildly successful Collaborative Management Day series suggests that for many bureaucrats, the focus is still on the tool of collaboration rather than on a broader objective of employee learning.

Not everyone has to participate to get value

Dan Pontefract also made an important point that not everyone in the organization needs to participate in social media tools for them to have value. He said that they are proud that about 1/6 of all team members are active on their microblogging service. That does not seem like a very high proportion, but he said it is important for people to find their own value in the service and whether they want to use it, which brings me to the last important point;

Don't mandate the use of social media, empower people to use it.

Nobody wants to use a tool if they feel they cannot get any benefit from it. And mandating them to use it only builds frustration and resentment. So instead, find ways to encourage people to use it.

To wrap up, this is a very informative interview with Dan Pontefract, and would recommend it to anyone interested in knowledge management, learning or collaborative technologies.

Telus is not unlike a lot of other organizations, including my own, who have put in place collaboration tools like wikis, forums, blogs, filesharing, instant messaging to promote the exchange of knowledge. But a few things about Dan Pontefract's presentation really struck me.

It's about Learning, not just collaboration

For me, the key point in Dan Pontefract's presentation is that collaboration technology is intimately connected to employee learning. By creating platforms like team collaboration sites, blogs, microblogs, videosites and wikis where employees can share ideas, opportunities and issues, employees are continuously learning from one another. He sums it up well when he talks about the "Learning 2.0 Model" at Telus. "Learning", he says, "is part formal, part informal, and part social." At Telus social learning is facilitated through social media. Eventually, as people begin using the technology, they get into a rhythm of how they start sharing and how they start exposing their content, their knowledge and their ideas. Ultimately, he argues, people realize quickly that what they gain from everyone else helps them do their job faster, better and in a more engaging fashion.

Note, however, that while Social media is facilitating one type of learning at Telus, it has not replaced other more formal and informal modes of learning - the so-called "sage on a stage". Formal and informal learning, no doubt, continues to play an important role in Telus' employee learning strategy.

This is not the first time I have seen Web 2.0 collaboration tools linked to employee learning strategies in organizations. At a recent conference on knowledge management, I met the director of learning for Rogers Communications, who told me a very similar story about what they are doing. As with Telus, social learning plays an important part of their employee learning strategy, but it is linked to formal and informal methods of learning. A similar story was told by Sierra Wireless at the same conference.

What really strikes me in these examples is the connection of collaboration to employee learning. In other words, collaboration is a tool, a means to an end that facilitates learning, but collaboration is not the objective. The objective is to create a learning organization.

Meanwhile, in government these days, I see a lot of attention being paid to social media and collaboration, but I have not yet seen this formal link to employee learning strategies. So, while we have wikis, blogs, forums, video sharing sites, file sharing sites, and other tools, and while timely access to information is routinely touted as the key benefit, it is not at all clear that this is seen as a form of social learning or how this social learning is linked to more formal and informal learning in each employees learning objectives. In fact, I wonder if recent events like the wildly successful Collaborative Management Day series suggests that for many bureaucrats, the focus is still on the tool of collaboration rather than on a broader objective of employee learning.

Not everyone has to participate to get value

Dan Pontefract also made an important point that not everyone in the organization needs to participate in social media tools for them to have value. He said that they are proud that about 1/6 of all team members are active on their microblogging service. That does not seem like a very high proportion, but he said it is important for people to find their own value in the service and whether they want to use it, which brings me to the last important point;

Don't mandate the use of social media, empower people to use it.

Nobody wants to use a tool if they feel they cannot get any benefit from it. And mandating them to use it only builds frustration and resentment. So instead, find ways to encourage people to use it.

To wrap up, this is a very informative interview with Dan Pontefract, and would recommend it to anyone interested in knowledge management, learning or collaborative technologies.

Labels:

collaboration,

KM,

learning organizations,

social learning,

Web2.0

Wednesday, May 4, 2011

Les ressources pour la formation française

La semaine verte - une quotidien de Radio-Canada. Cherche saison 32/episode 32 pour une episode au

sujet de la forêt au Québec.

Audio comprehension exercises:

French tests and resources at french.about.com

Translation:

- wordreference.com

sujet de la forêt au Québec.

Audio comprehension exercises:

- Campus Direct (audio and transcripts)

- Oral exercises in French (listening and comprehension test)

- audio comprehension excercieses from pointudefle

French tests and resources at french.about.com

Translation:

- wordreference.com

Wednesday, March 9, 2011

Blogging for knowledge workers: organizational storytelling

Blogging within corporations and organizations has become fantastically popular. Within my own organization there are dozens of blogs that I know about.

Blogging is done for many reasons, many of which are described in two great posts by Lilia Efimova:

But what role might corporate blogs play in organizational storytelling?

Organizations, cultures and societies are sustained by stories and our attempt to understand and negotiate the world is grounded in narrative. Storytelling translates bare facts and logical argument into a form with which people can engage – both emotionally and intellectually. A good story is the simplest and most powerful way to create a desired future. It is the story that guides us in our day-to-day interactions. It is the story through which knowledge is created, stored and passed on. While people may come and go in the organization, it is the story that remains to remind people who they are and where they are going to.

According to Storytelling.co.za, Organizational storytelling comes in two distinct flavours; the life stories of the individuals that comprise the organization and the organizational narrative. It is important to engage both; the stories of individual employees are useful in understanding the unique organizational 'diversity mix' and the organizational story creates context for day-to-day experience.

Individual narrative engages stories from the front lines with themes such as 'here's how I do things, this is my experience, opinion or judgement". While stories are widely told in the workplace (around the water-cooler, for instance) there are relatively few places for individuals to tell their story to a larger audience or to record their story. An internal blogging platform that is easy to use, available to all employees, and searchable by corporate search engines could be a powerful way to capture and share tacit know-how held within the organization.

Organizational narrative engages stories with themes such as 'what is going on?, who we are? what do we sell? how we do things here, where we are coming from and where we are going to'. These are profoundly important stories and they need to be deliberately told and controlled by leadership. An internal blog regularly updated by senior managers could be a powerful way to pass on those stories and engage staff in a conversation about what those stories might mean for the work of the organization.

Blogging is done for many reasons, many of which are described in two great posts by Lilia Efimova:

- Blogging for knowledge workers: incubating ideas

- Blogging for knowledge workers: personal networking

But what role might corporate blogs play in organizational storytelling?

Organizations, cultures and societies are sustained by stories and our attempt to understand and negotiate the world is grounded in narrative. Storytelling translates bare facts and logical argument into a form with which people can engage – both emotionally and intellectually. A good story is the simplest and most powerful way to create a desired future. It is the story that guides us in our day-to-day interactions. It is the story through which knowledge is created, stored and passed on. While people may come and go in the organization, it is the story that remains to remind people who they are and where they are going to.

According to Storytelling.co.za, Organizational storytelling comes in two distinct flavours; the life stories of the individuals that comprise the organization and the organizational narrative. It is important to engage both; the stories of individual employees are useful in understanding the unique organizational 'diversity mix' and the organizational story creates context for day-to-day experience.

Individual narrative engages stories from the front lines with themes such as 'here's how I do things, this is my experience, opinion or judgement". While stories are widely told in the workplace (around the water-cooler, for instance) there are relatively few places for individuals to tell their story to a larger audience or to record their story. An internal blogging platform that is easy to use, available to all employees, and searchable by corporate search engines could be a powerful way to capture and share tacit know-how held within the organization.

Organizational narrative engages stories with themes such as 'what is going on?, who we are? what do we sell? how we do things here, where we are coming from and where we are going to'. These are profoundly important stories and they need to be deliberately told and controlled by leadership. An internal blog regularly updated by senior managers could be a powerful way to pass on those stories and engage staff in a conversation about what those stories might mean for the work of the organization.

I have seen numerous examples of individual narrative captured on blogs, but I have seen only a few examples of organizational narrative effectively told on corporate blogs. If you have examples, I'd love to hear about them.

Thursday, March 3, 2011

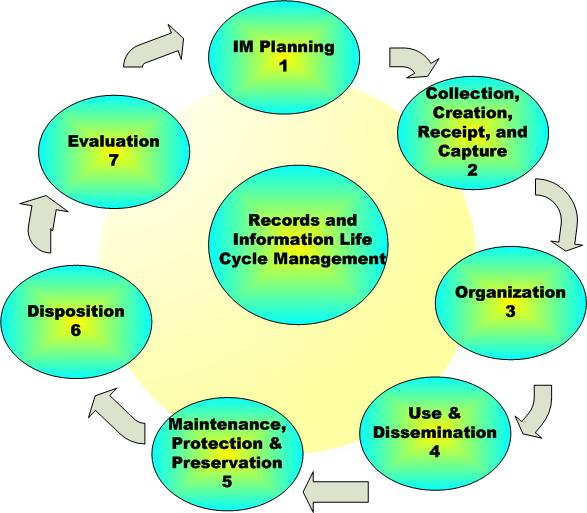

Implementing the Information Life Cycle

Library and Archives Canada has been promoting its Records and Information Life Cycle as a means to help users understand, plan, implement and improve their Information Management (IM) initiatives

|

| copyright: HM Queen in Right of Canada |

Accordingly, a year or so ago, we conducted a survey of 22 creators and users of scientific information to see which parts of the life cycle they regularly apply in the management of their own information.

Through a series of detailed questions, we asked respondents whether or not they thought each stage of the cycle was applicable to their information management needs. If it was applicable, we asked them whether or not they had planned to address that stage of the life cycle and the extent to which they had actually implemented any planned activities.

|

| Copyright HM Queen in Right of Canada |

The survey revealed that most respondents had initiated activities to plan for information needs, collect, create, receive and capture information, organize information, and use and disseminate information. However an increasing number of respondents had not planned for the maintenance, protection and preservation of their information, the disposition of their information after they were finished with it, or to evaluate the effectiveness of their IM practices after the project was over. This was valuable information in telling us where we needed to direct our efforts.

Recently, I reanalyzed the results to better understand where we could use internal expertise to improve the management of records and information, and where we might need to draw on external expertise.

First I scored the respondents answers using the following scale: 0 = Not Applicable, 1 = Not Planned, 2 = Planned but not initiated, 3 = implemented and up to 25% complete, 4 = implemented and up to 75% complete, and 5 = implemented and 100% complete.

|

| Copyright HM Queen in Right of Canada |

Using Chris Collison's River diagram technique, I then plotted the minimum and maximum scores among all respondents for each stage in the life cycle.The area shown in blue in the diagram above is the area between the minimum and maximum scores. The bottom bank shows the minimum level of attainment for each stage of the life cycle, the top bank shows the maximum level of attainment for each stage.

Collison suggests focusing on the widest parts of the "river" in order to leverage the most out of internal experience. The diagram shows that for stages 1 and 3 in the life cycle, everyone surveyed is at least planning to implement relevant activities for their information, therefore, these stages should not be priority areas to focus on. In stages 2, 3 and 6 some people have obtained a high degree of experience, having completed their planned activities for this stage, and it may be possible to share best practices.

For us the widest part of the river is at stages 2 and 6. By sharing their best practices or by pairing individuals who have completed their activities with those who have not even planned activities, there is great potential to raise the lower scores.

Conversely, at stage 7 there is no one who has completed all their planned activities. In this case, there is less internal expertise we can draw on and we may have to bring in external expertise to try and improve the scores.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)