There are ample reasons why science and policy are so difficult to integrate, and there is lots of good work being done to try and address this issue. But a recent half-day session with David Snowden gave me new inspiration into how one might tackle this particularly thorny issue.

If I have captured the parlance of Snowden's Cynefin framework correctly, then I think science-policy integration must be a complex problem. That is to say, a problem in which cause and effect are only coherent in retrospect and do not repeat, there are no right answers and many competing ideas, and where problems and solutions interact so the system is constantly evolving.

Snowden had a couple of pieces of advice that resonated with me when it comes to solving complex problems.

First, he says, don’t waste time trying to figure out what to do. Instead, probe with small experiments, then monitor and adapt. Since you cannot define what the ideal future state will be, start with a good definition of the present and move forward with safe-to-fail experiments that may lead to unforeseen outcomes. It’s cheaper and more successful. If you can accept that your theory for proceeding is coherent with the facts - with the way you understand the present - then you can move to a place where the outcome is uncertain. In other words, you have safety in direction, not safety in outcome.

Second, you need to monitor the experiments carefully, with impact indicators, not output indicators. In complex problems, argues Snowden, you cannot manage the outcomes because they are emergent. However, you can manage the boundaries of the issue you wish to deal with, the tools and processes you put in place to influence the patterns of behaviours in the system, and the resources devoted to amplifying positive patterns and dampening negative patterns. Snowden gave an example of how focusing on outcome indicators can derail solving complex problems. In the UK, a hospital authority decided that it was unacceptable to have people in the emergency waiting room for longer than 4 hours and in the emergency ward for longer than 48 hours. The result was that patients were not properly triaged or treated. They were pushed through the system and on to the wards based on how long they had been there, not based on their medical need. The quality of care did not increase, but the emergency room met its targets.

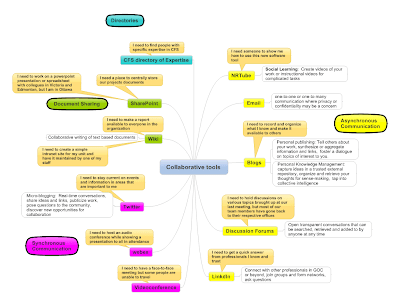

Third, it is really difficult to address complex problems directly. Instead, address them obliquely. Many complex problems are about changing organizational culture. But it is very hard to change people. Instead, argues Snowden, change the system and the people will change to match it. Nobody, for example, is going to share information across silos just because they had a workshop and were told they should share.

So what does all this say about developing evidence-based policy to strengthen science-policy integration when times are uncertain, and the ideal future state cannot be described?

Snowden gave a number of examples of work he has done to solve complex problems using self-indexed micro-narratives, which may be relevant to strengthening science-policy integration in an organization such as the one I work in.

At the heart of Snowden’s examples is a process by which people are asked to first tell a story about a particular topic and then to score or weight their story using a carefully constructed index. The stories are recorded in any number of formats: written, audio, video. The format is not important, as long as they are left unfiltered and are not summarized. The index is similar to keywords used to describe the story, but much more sophisticated. The index takes the form of a triangle on which the storyteller is asked to place a dot. At each point of the triangle are carefully selected keywords. The storyteller is asked to place the dot in the triangle closest to the word that describes their story. When the storyteller places the dot, it gives three quantitative weights – one for each choice between two points of the triangle. These weights can be used to plot the stories on a 3-D graph. Storytellers are often asked to score their story on several indexes, which can be recombined to create different graphs. Similarly scored stories show up as clusters on the graph.

Snowden gave an example of this technique from when he worked with the CIA in the ‘70s. The CIA funded an American university to work with a French University to study attitudes in Iran. The French University had some Iranian professors, and as part of the study the professors asked Iranians to tell them stories about Iran and then self-index the stories. After collecting about 18,000 stories, two clear clusters of stories emerged. One cluster was stories that related a strong dislike of America. The other cluster was stories that related a strong dislike of the West. This was not too encouraging, but they continued collecting stories. After 21,000 stories, a third cluster emerged. This cluster was comprised of stories that related the concept of not wanting to be seen as a barbarian. Snowden recognized that this was the opportunity for intervention; that if the US could somehow emphasize the later story, it might drain energy away from the other stories.

Snowden did not go into detail about what the CIA did, but he did give more detail about a project he is working on right now in Mexico City. This project is focused on changing the culture of violence associated with gangs and drugs. They have collected about 200,000 self-indexed stories from ordinary people on the street. When they analyze the stories, they are confident that a cluster of stories will emerge about the violent gang culture. However, they also believe that a number of positive stories will emerge. Once they find out what those positive stories are, they will work with experts in Hollywood to create films, TV spots, multi-media presentations, whatever it takes to emphasize the positive stories, and hopefully, drain energy away from the negative stories.

For Snowden, the culture of a society or an organization is wrapped up in its stories. If you can change the stories people tell, you have changed the culture.

So how does this relate to science-policy integration?

I think that strengthening science-policy integration within a science-policy organization is actually a culture change problem. So, what if we took this approach:

- Record stories from employees in the organization about their science-policy interaction experience and have them self-index the stories on carefully selected indexes (e.g. is the behaviour in this story best described as "competitive", "cooperative", or "altruistic"),

- Graph the stories to find clusters of positive behaviours that might represent opportunities to intervene.

- Develop and implement some safe-to-fail policies, guidelines, or tools to reinforce the positive behaviours and dampen the negative ones,

- Recollect stories, perhaps a year later, and see if the clusters of stories have moved one or two index points toward more desirable values. Resources are given to tools that seem to be working and taken away from the tools that are not working.

Success is measured by the index values of the stories, which measure the impact of the actions taken to influence the system. Success is not measured by output indicators, like the number of meetings scientists and policy analysts had.

There is obviously a lot of detail I am missing here, and I need to familiarize myself more with Snowden's techniques. But at first blush, this seems like a promising approach to strengthening science-policy integration in a complex environment.